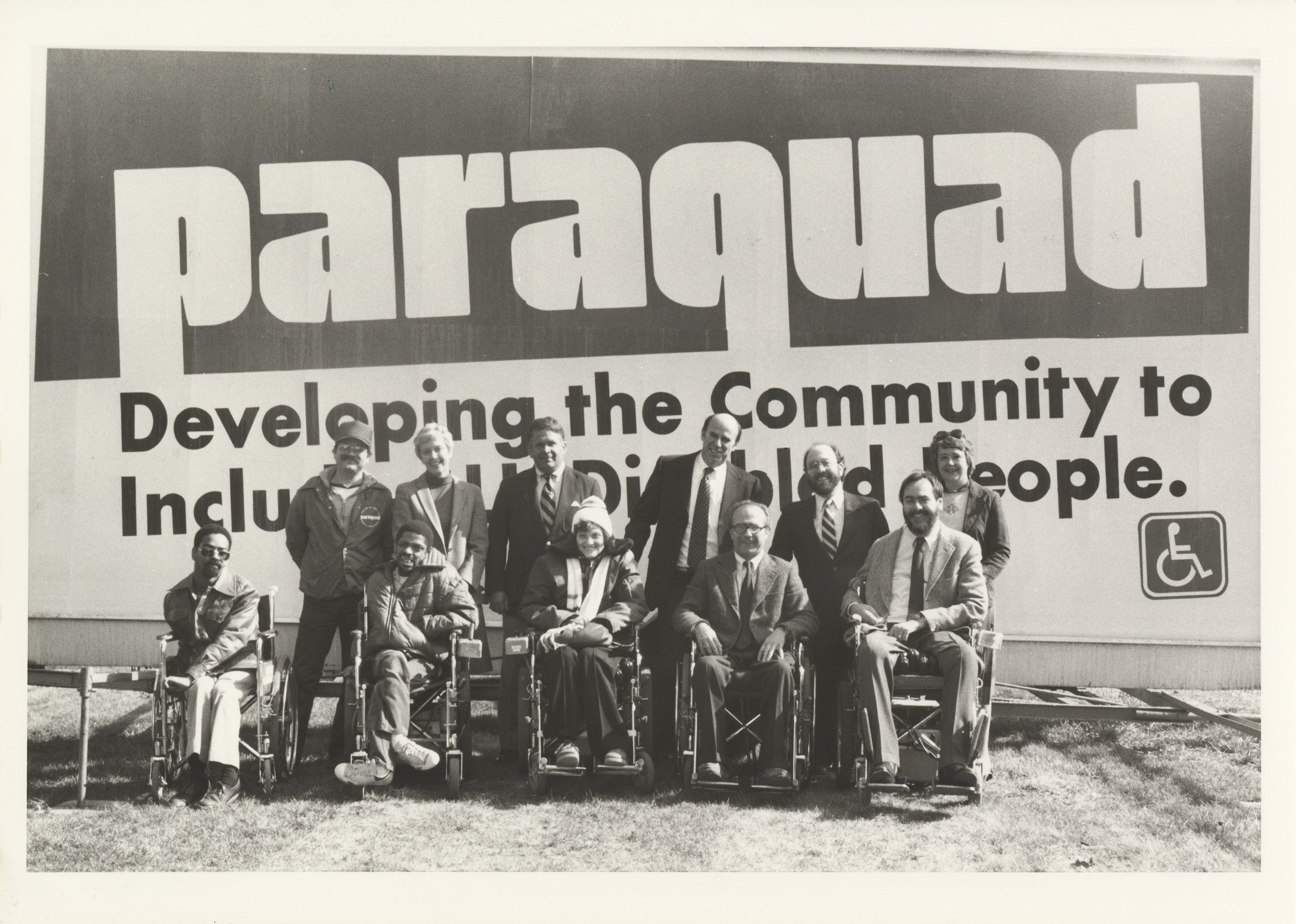

For 55 years, Paraquad has worked tirelessly to promote inclusion for people with disabilities in St. Louis and around the world.

History of Paraquad and the Independent Living Movement

-

1970- After beginning a search for services to help him move from a nursing home, Starkloff starts working on accessible housing. Paraquad is born.

1971- Paraquad’s first grant is funded by Morton D. May. Access studies and consultations begin with area businesses.

1972- First curb cuts completed in St. Louis.

1975- Education of All Handicapped Children Act passes, requiring free and public education in the least restrictive environment possible. This law is now called Individuals with Disabilities Education (IDEA) Act.

1977- St. Louis becomes the first city in the nation to have lift-equipped public buses.

1979- Paraquad officially becomes a Center for Independent Living and it one of the first 10 centers nationwide to receive federal funding. Jim Tuscher supported Max Starkloff in the formation of the non-profit and became one of the first staff members and was instumental in securing funding to bring 22 Centers for Independent Living to Missouri.

-

1980- An ad hoc group of the first 10 federally funded Centers for Independent Living meet in St. Louis and form what would become the National Council on Independent Living (NCIL).

1984- Missouri’s consumer-directed personal attendant services program is established in state law.

1987- Paraquad’s Youth and Family Program begins a youth group that includes disabled and non-disabled children, a first of its kind in St. Louis.

1988- The Fair Housing Act was amended to prohibit discrimination against people with disabilities.

1989- Paraquad’s Career Options and Employment program begins.

-

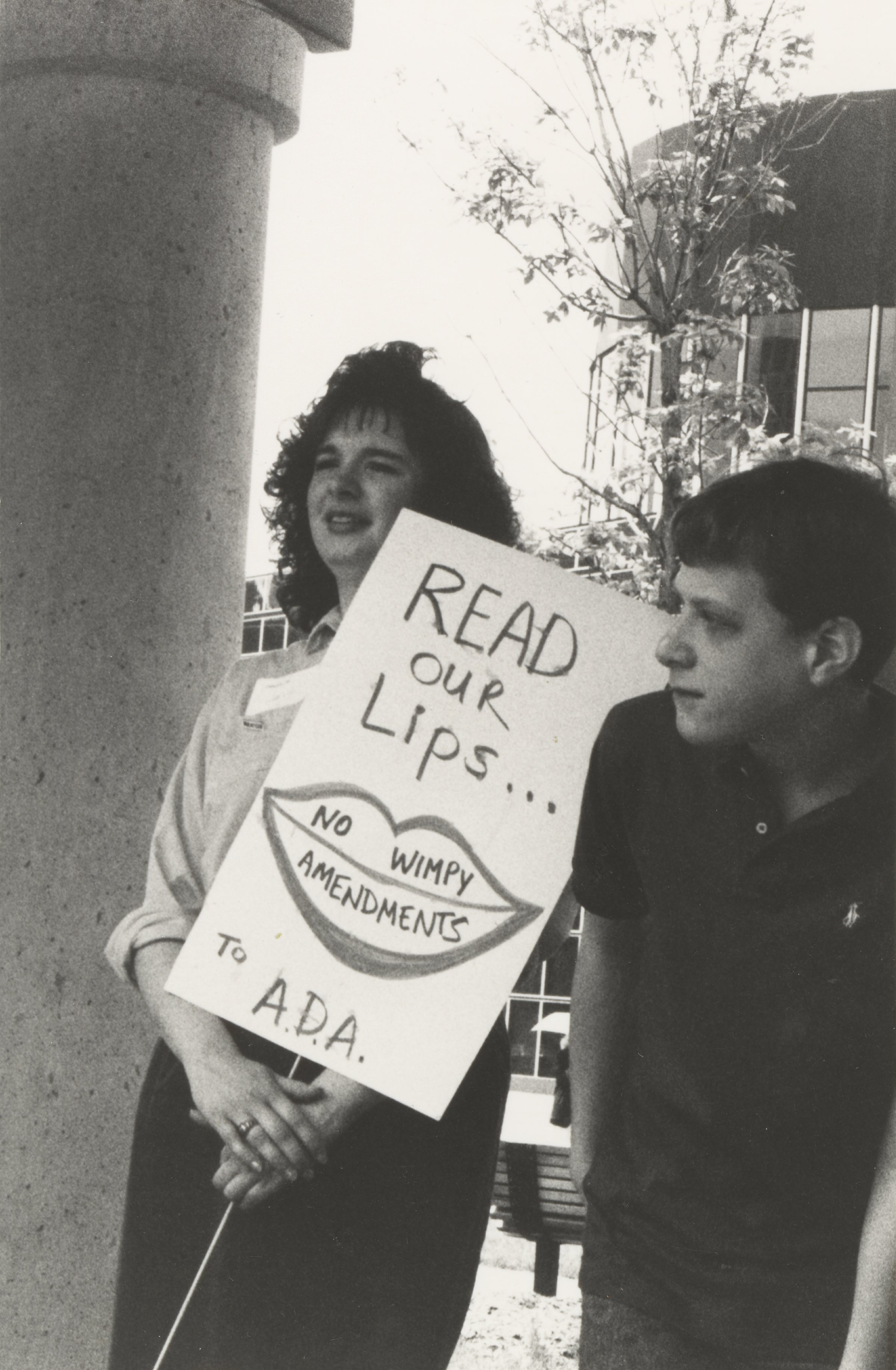

1990- The Americans with Disabilities (ADA) Act is passed and signed into law

1993- Public Policy becomes an official department at Paraquad.

1995- Max and the Magic Pill, a documentary chronicling Starkloff’s battle for accessible transportation, is produced by KMOV-TV and receives an Emmy Award.

1996- Missouri passes legislation permanently allowing disabled voters to cast absentee ballots.

1999- The United States Supreme Court rules in Olmstead vs. L.C. that the unjustified isolation of people with disabilities is discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities (ADA) Act.

2000

Paraquad organizes the first Missouri Youth Leadership Forum, brought on after Jim Tuscher learned about a Youth Leadership Forum for Students with Disabilities in the state of California during the late 1990s.

2006

Paraquad moves to its current location on Oakland Ave. in St. Louis.

2011

Paraquad dedicates The Jim Tuscher Auditorium. Tuscher was the former Paraquad vice president of Public Policy and a leader in the disability rights movement.

2012

Paraquad hosts its inaugural Shine the Light Awards and recognized businesses and people committed to accessibility in St. Louis.

2014

Paraquad announces plans for a new Accessible Health and Wellness Center that will feature more than 40 pieces of accessible exercise equipment and serve up to 500 people annually.

2015

Paraquad launches AccessibleSTL, a partnership between Paraquad and St. Louis businesses, organizations and government entities to create a more inclusive, accessible city.

2018

Paraquad opens Bloom Café, a social enterprise restaurant that serves a fresh take on casual dining while helping people with disabilities grow their independence through a unique job training program.

2020

The Health and Wellness Center received a generous gift from the family of Stephen Orthwein in his honor. This gift has been critical in transforming the Health and Wellness Center from a solid local resource to a state-of-the-art regional destination that provides transformative exercise options to promote independence and life-long wellness for people with disabilities.

About Max Starkloff

Story by RICHARD WEISS

Max Starkloff’s world changed forever on the night of Aug. 9, 1959, when his late-model Austin Healy Sprite convertible spun out of control and flipped on a two-lane road in rural Missouri. The accident left him a quadriplegic but not a victim.

Over the course of the next 50 years, Mr. Starkloff would emerge as a relentless, uncompromising force on behalf of disabled people. His advocacy earned him international acclaim. But many say it was his personal example that may have meant even more. Mr. Starkloff spent 12 years in a nursing facility before he was able to forge the independent life that he worked passionately to provide to so many others.

Mr. Starkloff was 21 when after attending a party with friends he lost control of his car near Defiance, Mo. He was handsome, athletic and a strapping 6’5″. To that point he had been living a carefree — and by his own account later — a rather irresolute life.

Doctors told family members after the accident that young Max would probably live only a few days. Still, something even then about Mr. Starkloff’s spirit suggested he would carry on, according to a biography by St. Louisan Charles Claggett.

According to Claggett’s biography, “Max remembered seeing his uncle talking with three other doctors. He saw a wood drill and felt numbness in his head. A priest was called in to give him last rites.”

To which Mr. Starkloff responded: “I don’t need those.”

-

BLEAK PROSPECTS

And he was right. But the world he would enter as a quadriplegic was almost irrepressibly bleak. There were no electric wheelchairs, no touch-tone telephones, no sidewalk ramps or other public accommodations for anyone on wheels. At the time, Claggett wrote, the only public laws regarding people with disabilities were designed to discriminate, such as Chicago’s Municipal Code 36-34, which forbade anyone with a deformity “to be allowed in or on the public ways or other public places in the city.”

The only jobs available for disabled people were largely menial and paid far below what others received for performing similar tasks.

After spending 138 days in the hospital, Mr. Starkloff was returned to the home of his divorced mother, Hertha Starkloff, in University City. There she acted as his primary caregiver with the help of aides while working a full-time job in real estate.

Mr. Starkloff learned to use the phone and, for a time, began selling insurance and entertaining his legions of friends who would come to visit. But the home care proved too much for his mother, who was then 57. The responsibilities were draining her both physically and financially.

At the time, the federal government paid $30,000 a year for nursing home care, but nothing to families who wanted to keep their loved ones at home. So on Oct. 23, 1963 — four years after the accident — Hertha drove her son to St. Joseph’s Hill Infirmary in Eureka, during which Mr. Starkloff remembered, “No words were spoken.”

As Mr. Starkloff recalled for Claggett’s biography, “This was it, the end of the road. I was going where people go to die.”

But in fact, it was at St. Joseph’s Hill where Mr. Starkloff found a purpose and meaning in his life, and not incidentally his wife.

THE LIFE-ALTERING DREAM

At first, Mr. Starkloff passed the hours at St. Joseph’s by creating a rich fantasy life. “I would create a family, give each member a name and how each person looked,” he told Claggett. “Sometimes I would create baseball teams, memorizing imaginary players their batting statistics, wins and losses.”

Later, Mr. Starkloff would use his imagination to create works of art. He met a Franciscan brother who taught him how to manipulate a paint brush, using his teeth. For the next several months, Mr. Starkloff would work in the infirmary studio for six hours a day. Mr. Starkloff’s paintings were shown in exhibitions, written about in the local press and they created an income.

Even so, Mr. Starkloff chafed at his lack of independence. He remembers the bus tours that would come to St. Joseph’s Hill where he would be shown off to the visitors. A Franciscan brother would bring the tour to Mr. Starkloff’s room while he was lying down and invite them in to see his paintings.

Claggett wrote: “Tousling Max’s hair as though he was an obedient dog, Brother Patrick would exclaim, ‘Isn’t it amazing? He actually holds the brush in his teeth! Considering how he paints, I think Max is pretty good,’ he’d beam.

“Departing, several of the women would pause, look down at Max and say, ‘Isn’t it nice that you have something to occupy your time?'”

Over the years, Mr. Starkloff began to read up on and get in touch with other people with disabilities and those who were advocating on their behalf. One was Gini Laurie, who asked him point-blank, “What are you doing in a nursing home?” Laurie, who was blunt and outspoken, often would say, quadriplegics “need a pair of hands that they can direct. They do not need to be buried alive in a nursing home. They need to live their lives as they choose.”

By 1970, Mr. Starkloff had given up painting and devoted himself to what he called his “life-altering dream.”

“I dreamed of an apartment complex built for people with disabilities in which they could live and work,” he told Claggett. “It was a utopian environment for people with disabilities where they could also be entrepreneurs. And it wouldn’t just house people with disabilities. Anyone could live there.” He would later name it the Para-quad project.